Honestly, there’s nothing particularly novel about the topic of this post: using RSS feeds to keep up with the scientific literature. The technology has been around for ages. Nature Chemistry actually has a nice editorial on this subject (among other things) from a couple of years ago, and many library websites offer advice. So file this post under “advice for new grad students in my group that could be of interest to others”. If you already have a good RSS workflow I’m not sure there will be a whole lot on offer here. However, if you don’t, you really owe it to yourself to consider switching over. Perhaps as part of a New Year’s resolution to better keep up with the literature?

While not at all uncommon, RSS (“Rich Site Summary” or “Really Simple Syndication”) never really made it into the mainstream the way it should have. It’s the sort of thing my mom should be using but doesn’t (at least not deliberately). Its usefulness is probably best illustrated by example. Let’s say you were to subscribe to the RSS feed for this blog, which you could do using the linked RSS logo at the top right of the site (next to the Twitter logo) or the links at the bottom right of the sidebar. To do so all you would need is some sort of RSS aggregator app, many of which are available for all platforms. The net result would be that every time I published a new post you would receive a notification in the aggregator. In the case of this site you’d just get the whole post; for other sites you would get a bit of a teaser with a link to the full content.

On some level an RSS subscription is a lot like getting an e-mail every time new material is posted, except 100% less awful. RSS feeds are the easiest way to keep up with websites, like blogs, that are regularly updated and for which you want to be made aware of every update without having to manually check back every day. It’s not really right for every site. The New York Times offers RSS feeds, but I stopped subscribing to them years ago because it makes more sense for me to just check out nytimes.com periodically to see what the current headlines are. Even when broken down into smaller categories I’m not interested in being notified of the many articles they publish one-by-one. On the other hand, I do subscribe to the Ars Technica feed because they publish a manageable number of posts and, even though I might only look at one or two per day, I like quickly scanning through the titles.

Of course, for a scientist blogs and news sites are fine, but the most important sites with periodic updates are those for the literature itself. Back in the dark ages, I kept a paper list of journals—a new sheet for each year—and I’d just track issue numbers as I went through them. Honestly, it was less than ideal, mostly because it meant that I would only browse the literature if I had time to go through a complete issue. Some of the “less-impactful” journals got less than my full attention. The advantage of RSS feeds is that they track individual articles. If I have 5 minutes to spare before a seminar I can skim through a few, flagging the ones I want to take a closer look at later.

My first foray into RSS feeds some years ago used the excellent Vienna as my feed aggregator. However, much like e-mail, a stand-alone RSS reader tied to a specific PC gives up too much convenience. Having RSS subscriptions synced through the cloud is much more powerful. Honestly, I’ve probably browsed through as many articles sitting on a couch at the mall as just about anywhere else.

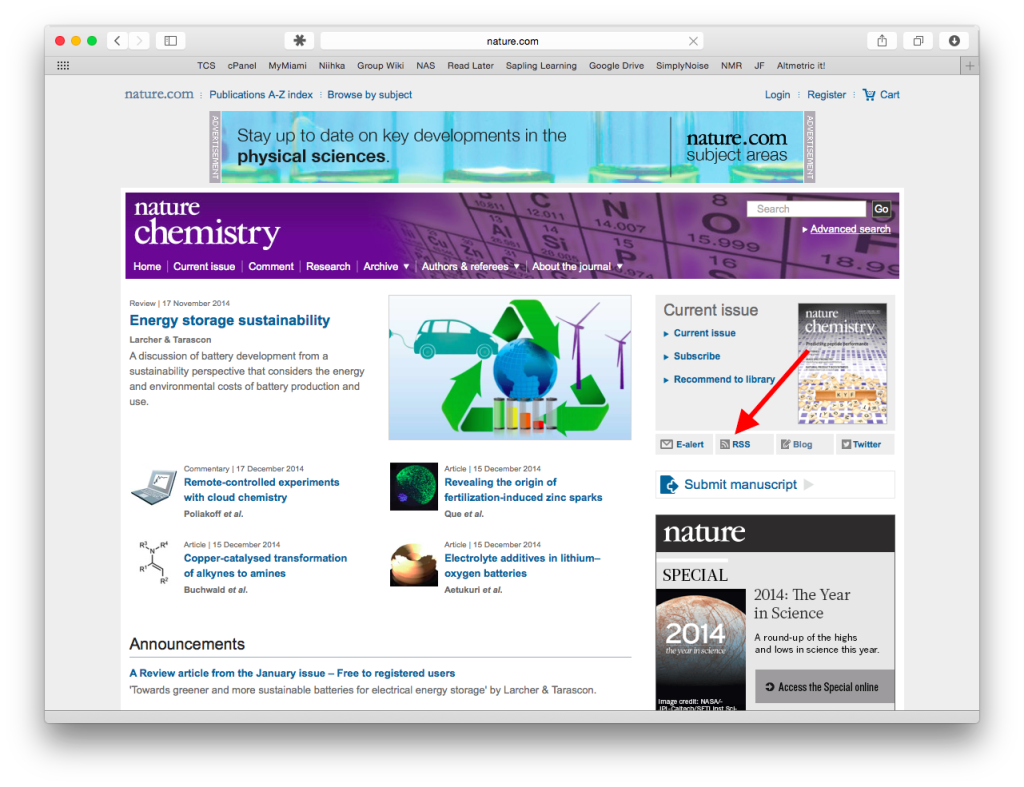

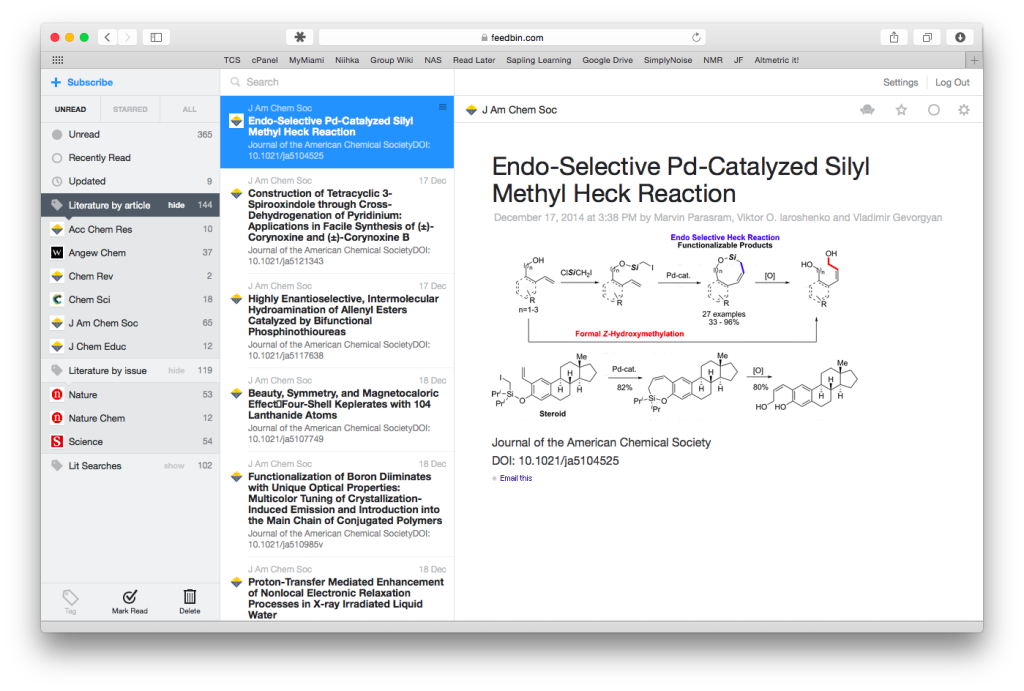

Like many others, I used the Google Reader service for this purpose for many years. Alas, Google giveth, and Google taketh away, and we all learned a valuable lesson about using free services with no obvious route for Google’s monetization. After Google Reader’s demise, I wanted to switch to a similar service but, for something so important to both work and leisure, I wanted a paid system that I could count on. I ultimately settled on Feedbin. It’s reasonably priced for a service I use almost as much as e-mail (a few dollars a month). Here’s a screenshot of the web interface:

Feedbin’s web interface. Note to Hartley Group members: I read more journals that this, these are just the ones that happened to have unread articles!

I have journals organized into two categories: those that release articles sporadically (most of them) and those that tend to release complete issues all at once with various commentary pieces (e.g., Nature, Science, Nature Chemistry). For the latter I like to look at complete issues, whereas for the former I don’t care if all the articles are jumbled together. Feedbin also has an excellent mobile interface:[1. Truthfully, I rarely use the web interface for Feedbin and instead use Reeder as a client.]

Feedbin’s mobile interface. You can’t see it, but scrolling down slightly reveals a link to the next item in the feed.

Of course, this isn’t an ad for Feedbin. I’ve been quite happy with it, but there are many other options. A quick Google search for RSS readers yields many (including free) options.

Actually subscribing to the RSS feeds for journals is straightforward, and does not require institutional subscriptions.[2. Of course, you need the subscription to actually read the full text. Otherwise you’ll need to purchase or request through interlibrary loan.] Most journals offer easy-to-locate links to their RSS feeds, and it’s simply a matter of pasting these into whatever aggregator you are using. Here’s an example from the Nature Chemistry website:

It’s of course impossible to go through every issue of every journal relevant to one’s field, and I’ve had to cut back on the journals I look at as I’ve gotten more busy. Conveniently, it is also possible to set up RSS feeds for literature searches through Web of Science, PubMed, or whatever your preferred lit-searching-service is (unless, sadly, it’s Google Scholar, as far as I can tell). These sorts of searches provide a nice way to get some depth while you’re browsing mostly for breadth.